Episode 10 - Marilyn Maney

Welcome to Mining City Reflections, where we illuminate the history of Butte, Montana through the stories and observations of 20th century women who lived there. I'm your host, Marian Jensen. In this episode, we continue the story of the Women's Protective Union, a 20th century labor organization in Butte that captures the essence of the Mining City spirit. We'll hear from Marilyn Maney, one-time chair of the Board of Directors of the Butte-Silver Bow Archives. She was instrumental in the formation of its Labor History Collection and was uniquely qualified for the job, as she actually consulted with the last officers of the union.

“So that was like an 82-year history of all-female leadership and all female membership. That certainly was quite unusual in terms of the America labor movement, to have an all-female union like that.”

While in her early 20's, Maney had become acquainted with union leaders during the last years of its existence. She heard first hand about the union's work.

“Very interesting about the early years of the union, although it was not unusual for that time in Butte - is that they were were industrial unions. In other words, they did not organize by craft or trade. All that was necessary to be involved with that organization was that you were female and you were working outside of the home. In those early years, their members were waitresses, maids, bucket girls (women who made the lunches for the miners, packed their lunch buckets that the miners took with them on their shift). The majority of them worked in boarding houses and restaurants, small cafes, chamber maids.”

The women the union represented worked at what some would consider menial jobs, but their approach to labor organizing aligned with one of the most radical labor organizations in the country.

“They sent delegates to the founding convention in June of 1906 in Chicago of the IWW, Industrial Workers of the World.”

The IWW's influence in Butte met with controversy, and was marred by the infamous lynching of one of its organizers, Frank Little, in 1917. Members of the Women's Protective Union marched in the silent procession behind Little’s coffin. Val Webster, who would one day become a leader in the WPU, actually attended the funeral at the tender age of 5 with her mother.

The WPU concurred with the IWW's approach to trade unionism as a vehicle for social justice. They organized to help their members not just on the job, but also by providing housing options, as well as child care and health care.

“It actually functioned not only as a collective bargaining unit for their members, but it also functioned as really sort of a mini welfare agency., They helped their members secure housing. T Hey had what they called health and welfare - they had funds where they would help members if they needed medical care. They even had a fund that was set aside specifically to assist members with funeral and death services. They had a fund that was set aside to buy burial clothes or shrouds for members when their children died. They were that well-organized in terms of their social services.”

By 1904, the WPU had purchased their own building in the center of town on Broadway where members could go for a whole host of services.

“And that building belonged to the Women’s Protective Union; they bought that building. And it was three stories. On the first floor, they had their office and they also had rooms for teaching immigrant women English, helping them get ready for their citizenship test. They gave classes and instruction on - you name it - hygiene, everything. Then the upper two floors, they rented out to young immigrant women who had joined their ranks, who were working, so that they would have a safe and clean and protected place to live.”

Likewise, even before Montana women gained the right to vole in 1914, the Women's Protective Union supported a progressive agenda of what they considered important reforms in government.

“They were very progressive. As early as 1896, they were calling for things like social security, 8-hour day, minimum wage - probably forty years before Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Social Security Act.”

Eventually, the union became involved in women's suffrage and supported the candidacy of the first woman to serve in the United States Congress.

“They were involved in the campaign to get women the vote. And they did support Jannette Rankin when she ran the first time, even though she was a Republican. And then they were bitterly disappointed in Ms. Rankin and some of her anti-labor votes.”

After the Miners' Union strike in 1934, Butte entered an era of relative labor stability which benefited all the unions. After World War 2, the American economy experienced unprecedented growth. The Women's Protective Union membership felt their wages did not adequately reflect this prosperity. In 1948, the WPU called the one and only strike in its history. With picket lines honored by all the other unions in Butte, retailers and restaurateurs folded after seven weeks. All the WPU's contract demands were met.

The Women Protective Union membership thought first of their rights as workers. Their gender came second. No surprise then that the Equal Rights Movement of the 60s and 70s became contentious.

“It’s very clear in the memories and recollections and the actions taken by those women who ran the union for the last 20 years or so of its history (and probably for many years before that). They identified themselves primarily as workers. The fact that they were women put them in a special category and made it a little bit more difficult for them to earn their living, but they were primarilky workers. The Women’s Protective Union - Blanche Copenhaver, Val and those women who ran it - were violently opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment. They saw that as a destruction of what it had taken them 60 years to negotiate through labor contracts, as a way of recognition of women as workers, but workers in a special category with special needs. And they saw the Equal Rights Amendment as very damaging to the interests of working class women.”

Butte's status as "the richest hill on earth" described the value of the ore extracted and not, except for a handful of mine owners, its citizens. The mining industry attracted unskilled, often immigrant labor, where issues of class were ingrained, not only in the exclusively male miners but in the women who worked along side them. They had fought for their rights, could take care of themselves, and didn't need any other protection.

“Those women were bitterly opposed to the Equal Rights Amendment, as were most union or labor women. The reason being,m they had fought long and hard for those gender-based distinctions in the workplace about not having to lift 100 lb sacks, the 8-hour day - all of those restrictions that were put on employers in terms of what they could legally demand of their workers, particularly women workes. They saw the ERA, rather than an instrument that was going to advance the status, station and equality of all women - it was an instrument to advance only those upper middle class and professional women. There was nothing in it that would benefit them. In fact, they would lose if it were enacted because many of the regulations and the laws that had fought so bitterly for over the years would be negated by the Equal Rights Amendment.”

A great irony of the civil rights era came in 1973 when the Women's Protective Union, a well organized, highly successful and deeply committed organization for the advancement of women workers, was forced to allow men to join. The leadership of the union at the time were vehemently opposed to this requirement for what they considered two practical reasons.

“One of their biggest objections was, of course as everyone knows, although only women will admit: men are much too emotional and tend to get very angry, fly off the handle - it was going to complicate negotiations. And the other one, my very favorite, was that it was going to make it much more difficult to run the union effectively because men can really only work 8 hours a day. Women are used to working an 8-hour shift and then going home and working another 8 hours and so it was no problem for them to devote those extra hours to union work. But as we all really know, men can only work 8 hours and so it was going to make it really difficult to get anything done with the union.”

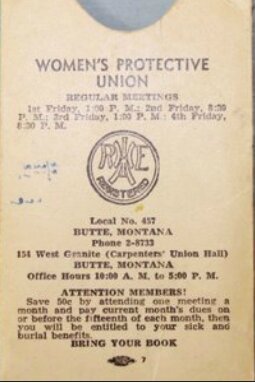

Objections aside, the membership faced the loss of recognition by other unions and sanctions by the U.S. Department of Justice. Their only recourse was to merge with the all-male waiters' and bartenders' union to form what became Chapter 457 of the Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union. In Maney's estimation, the WPU members cherished most their status as workers, and that they felt they could hold their own in the Gibraltar of Labor.

“They talked essentially about the identity and the pride that they felt as workers, which was not something that we as a society, as a nation, are used to recognizing - a women’s identity as a worker.”

“And that understanding of class - and how that functions in this community and how people defined themselves by class. Which oftentimes has been very out of step with the way the rest of America undestands themselves and understands what America is and what that means. That working class culture. There is a definite culture that goes with those working class values that are very often completely out of step with the dominant culture.”

The history of the Women's Protective Union bears witness to the tenacity and determination of Butte working women, qualities that permeate the community to this day.

“The impact that those women had on this community and on the working class women in this community, and by extension to a whole generation of women out there who, like myself, were not aware that as working class women we had that heritage. That we had that example of working class women coming together, organizing, operating in a very meaningful way to improve their lives and the lives of their community.”

“You know, it was like a club. Well, it was your family.”