Episode 8 - Anna Marinovich

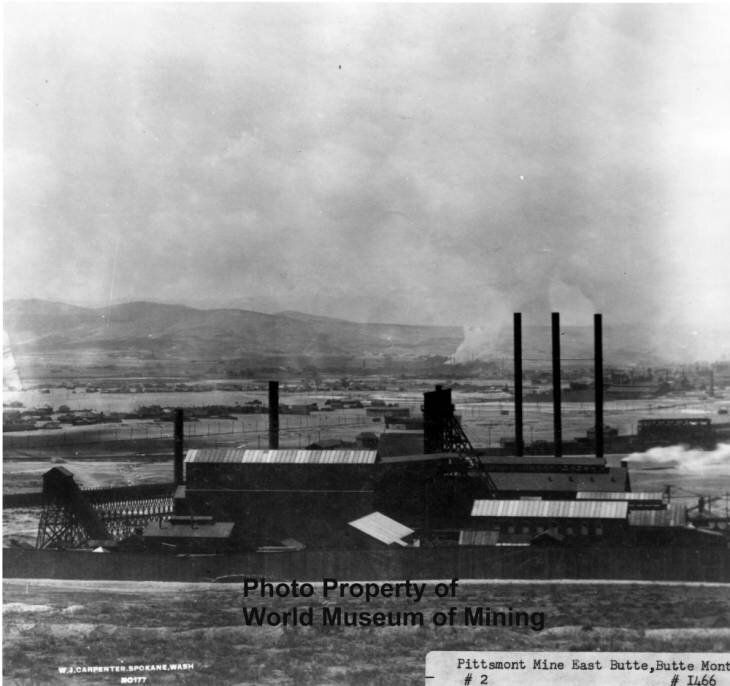

The Pittsmont Mine & Smelter where Anna would deliver lunch buckets as a kid.

Welcome to Mining City Reflections where we illuminate the history of Butte, Montana through the stories and observations of 20th century women who lived there. I’m your host, Marian Jensen. The oral history collection in the Butte Archives has preserved the personal recollections of these women in vivid detail. They bring to life the challenges and achievements of the boom to bust town.

In this episode of Mining City Reflections, we’ll listen to excerpts from an oral history of Anna Stefanac (Marinovich) who was born in 1901. Montana historian Mary Murphy interviewed Anna at her home in Butte in 1980. Despite hardships including harsh working and living conditions, the Marinovich story is one of delight and gratitude. A jovial woman with a knack for storytelling, Anna’s recollections reflect the gusto with which she lived her life.

“I was a little rascal right from the beginning.”

Poor economic conditions in Croatia and Slovenia led to an influx of immigrants from those countries. Anna’s parents, George Stefanac and Agnes Rauch, met in the Smelter City of Anaconda, Montana.

Speaking no English, Agnes had traveled alone from Slovenia at age 16 to marry an older, wealthy man, sight unseen. The match arranged by her mother brought the teenager to hysteria. She refused to marry, and was relieved to get a job as a maid in a boarding house instead. It was there she met George, a Croatian immigrant.

“This Mrs. Schute had a boarding house, if you please, and had to take in mother for a maid. And bless my father was there boardin’. And just because my dad was jolly and loved to sing and dace and joke (never had a rusty penny). And in fact my mother bought his wedding suit for him, really and truly. The little waltzes on the kitchen floor at 71 Plum St, that’s how we learned to dance!”

Eventually, the couple married and moved to East Butte so that George could work in the mine, as work in the smelter had affected his lungs. Her mother began taking in boarders to make ends meet, and to have enough food to feed her growing brood.

Often solitary men who had temporarily left their families for the high wages in the Mining City, many of the boarders treated the nine Stefanac children like their own.

“Boarders that mama had, they always wanted to be where there’s small children because they felt like they were family. A couple of them did, you know. They just loved children and they were so good to all of us kids too. Every time payday come, you know, two bit (50 cents), that was big money in them days. We thought the world of that, and they’d bring us candy home and stuff like that.”

The mines ran three shifts a day. Someone was always in need of a meal, which meant endless duties for Anna in the kitchen.

“Three shifts, you know. 11-7, 3-11 and 7-3 in the afternoon. Nothing but washing dishes, pots and pans, peeling spuds and cooking all the time! Really! you know? And changing dideys in between you know [laughs]. We had the babies running around too, you know.”

As the oldest child, Anna’s responsibilities helping her mother took precedence over going to school. Not that Anna seemed to mind.

“I didn’t even graduate the 8th grade; I was going into the 6B when I quit school. I don’t know what it was to go to 7 or 8th grade. I never graduated. People say how come you never graduated? I was so damn smart, I says hells bells, I says they told me to just go. I was, uh how do you call one of those? Genius! I had so much brains they let me go!”

Anna’s role in the boarding house included delivering lunch buckets to her father and their boarders when work at the mines was sporadic. Here we get Anna’s firsthand account of the conditions on the hill.

“I helped all I could, you know. And then the Big Ship, my dad was working as a watchman after he got through with the work in the mine a while, he worked in the Pittsmont Smelter. And I was on the blast furnace on the Pittsmont. See, they used to have little layoffs in the jobs, just like they do here. And then you’d have to go up everyday to the office to see because nobody had telephones or anything. So my dad would say, well (my mother’s name was Agnes but he called her Neja), if I’m not gonna be home in a half an hour, send Annie up to me with the bucket. Sometimes I had a couple of buckets up here and here and I was holding them and going. The boarders were at the job. So by god, if they knew I was on the blast furnace, oh god my dad with that muscle. And he was breathing heavy because he was short winded, you know, that thing. But you had to, that smoke was so thick. You know you see the smelter is over there. These hills are only now - since the smelter’s closed down for 50 years or more - these trees are coming back; otherwise everything was burnt.”

No task was too daunting for Anna. She enjoyed the challenge of pinching coal from the train yard, so much so that the railroad watchmen knew her by name. Though coal was cheap, every extra bit helped to boil the water to wash clothes all the faster.

“It was just cold. We had to get the boilers and heat the hot water. Otherwise you never wash clothes. And then poor mama used to make her own clothes to boot, you know.”

In her teenage years, life at the boarding house began to wear on Anna, whose mother kept a close watch on her. She began to think about a different future. The story of Anna’s courtship with Tom Marinovich reflects her determination.

“This is why I got married so young. I’m gonna tell the Gospel truth, like I say, right hand to god like little Annie Thomas used to say! God strike me dead if I’m telling a lie! [laughs] I was working, she won’t even let me know visit Hilda Benson, can’t go out of the house no place. My god almighty! Then one time I saw Tom, which I’m glad I did, I never made no mistake, you understand. I met him in October and I married him in December. And I never had one blasted date to go out with him alone. I was kept right in the house.”

Tom was resolute about marrying Anna. His English was not good but he wasn’t going to give up. Conniving to become a member of the Stefanac household, he switched places with one of their boarders.

“He come over to my mother and he asked for boardin’. She says no, I got no room; it’s all full up, no beds no nothing. “Oh yes, Mr. so-and-so today, he leave you house, you know?” [said Tom] “And I know you got for one.” So my mother was stuck so she says alright, come in the house.”

Sparking ensued in the stairwell, no less. But Anna’s mother was suspicious.

“7 o’clock, time to get up! Tom was waiting in the middle of the steps close to the down below. And he grabbed me and hugged me and mugged me. [laughter] You know? And mama wanted to know why I was so long waking up the boarders. I said, well I couldn’t wake up that one guy. I guess he was out; I was making excuses because I was smart too. I said he must have been out boozin’. He was hard to wake up.”

Eventually the trysts led to more.

“In the evenings, you know, it was November and December at 5:30 or 6 o’clock it would start getting dark, you know. And he had to be on the job at 6 o’clock, so he’d tell me if I would please sneak out the back door and come around the front of the house. He wanted to ask me something, you know? And that’s when he proposed to me.”

Anna refused to meet that first night but soon the pressure became overwhelming. Tom drew on ‘old country’ customs to convince Anna’s parents to let them marry.

“So he bought my mother a five-pound box of candy. And he bought her a string of pearls. He bought my father a box of cigars and a gallon of wine and a gallon of Rakie.”

Anna’s father was soon won over, for he liked his future son-in-law from the start. But her mother would not relent, fearing the loss of her daughter’s hard work in the boarding house. Tom finally felt compelled to speak up.

“My mother said no, she’s too young and she can’t get married yet. So then Tom says, “She likes me and I like her and I would like to get married.” Then he spoke up and he says, “How long do you think I am going to wait?” My mother said right away, “Till she’s 25 years old.”

George Stefanac finally agreed to the union, and the couple were married December 29, 1918 in Holy Savior Church, four months short of Anna’s 18th birthday. The wedding celebration lasted for three days. No one was happier than the newlywed groom who had known all along he had competition.

“He grabbed a hold of me, he lifted me. because, what the hell he was a strong man. Big husky body and big-built you know. He said, you know he said it in our language, “You’re never gonna be sorry. I’m the happiest man in all the world that you say you’re gonna be mine!” See, because there was a couple of other guys who wanted me, and he wasn’t sure. He said I was always a-scared. I told him I had to think it over. And he told me right to my face, “You don’t wanna think it over because you’ll promise somebody else maybe.” So when I told him, oh my god. He says, now he went like that. He put his bucket down just like that and he said, “I’m the happiest man in the world. Tonight 8-hour shift is gonna be like a 15 minutes for me.” He says, “I’m so happy that I won’t even know that I’m down in the mine!”

We can only imagine how many times similar stories played out among the young, lively residents of the Richest Hill on Earth. Tom and Annie set up house on Ash Street in McQueen and raised three sons. And Anna continued to help her mother.

Tom worked for the Anaconda Company for more than 45 years. They had 8 grandchildren and 12 great grandchildren. Tom died in 1975. Anna would live nearly another twenty years. The irrepressible Anna Marinovich died in 1994 at the age of 93.

“Come Christmas and holidays we had Christmas tree and lots more eats and lots more drinks you know. Yeah, it was really a nice life, I think.”

Mining City Reflections is a production of KBMF-LP and has been funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Permission for these recordings has been granted by the Butte Silver Bow Archives, the Montana Historical Society and the University of Montana.