Betty Lester, Career Elementary School Teacher

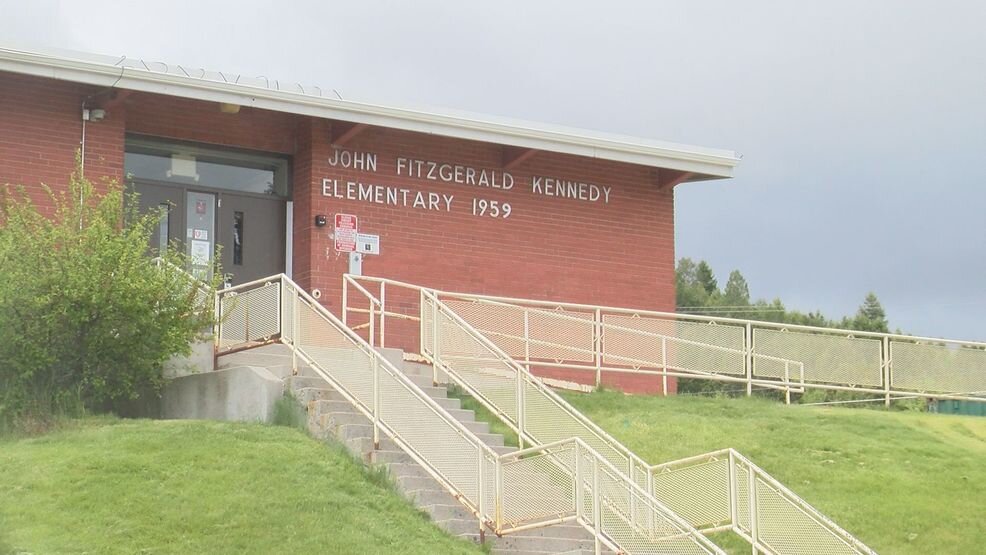

Kennedy Elementary in Butte, Montana. Photo by NBC Montana

Oral History Transcript of Betty Lester

Interviewer: Aubrey Jaap

Interview Date: June 14th, 2018

Location: Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives

Transcribed: July 2019 by Adrian Kien

Aubrey Jaap: OK, we’re rolling, Betty. So it’s June 14, 2018. We’re here with Betty Lester. So Betty why don’t you start telling me about your parents.

Betty Lester: My dad’s name is Paul William Jensen. My mother’s name is Madeleine Lena Irene Canonica-Jensen.

Jaap: So what did your dad do? Did he grow up here?

Lester: They’re Butte residents all of their lives. Well, they moved to Portland when I was older. They are like the first gypsies ever, because they would move in Butte from restaurant to restaurant. They’d get tired. They’d get workin’. Then, they’d go get another one.

Jaap: So did they sell the restaurants?

Lester: Yeah, and then they’d go get another one. And then they decided to move to Spokane and I asked if I could stay to finish my senior year at Central. And that’s a long story too. But they lived in Portland for the rest of their lives.

Jaap: So they owned restaurants?

Lester: My dad did go to Mount Saint Charles College. He quit when he was 6 months short of being a pharmacist.

Jaap: Why did he quit?

Lester: Who knows. He didn’t explain it to me. His dad owned Jensen drug.

Jaap: Where was Jensen drug?

Lester: OK, you know where the hospital is? Going up that first block there. It was there. I used to go there. His mother died when he was two. So he lived with my grandma Hoskins.

Jaap: So were you close with your grandma Hoskins?

Lester: Yes. I used to walk over from Nevada Street over to . . . I forgot the name of it. You’d walk over Second Street. It was on the corner of Dakota.

Jaap: So what did your grandma do?

Lester: She was a housewife.

Jaap: What did your mom do? Lena?

Lester: What do you mean what did she do?

Jaap: Did she work?

Lester: Yeah, she worked every day of her life. And she worked the restaurants with my dad, with your husband. They were both really the first gypsies. I called them gypsies, because they’d get going, have things right, decide they were bored and then start a new restaurant and a new place.

Jaap: That’s fascinating. You’d think you’d want to get settled.

Lester: There were a number of restaurants. They were really funny. The coolest restaurant when I was growing up was the Depot. The Northern Pacific Depot. I went to Saint Joseph school from 1st grade to 8th grade. I was probably in 7th and 8th grade when they had the Depot. And I would walk over at lunch. And lunch was an hour from 12:00-1:00. I’d walk over to the Depot for lunch. We walked everywhere then. Cars weren’t available. My dad had a car and if I asked for a ride, he’d say to me, “You have two legs.” Unless, it was a big long ride and I had to get there in a hurry. He wasn’t mean or anything. He just thought it was better for us to walk.

Jaap: So was there a restaurant in the depot?

Lester: I was in 7th and 8th grade and I’d walk over to the Depot. There was a magazine counter. I’d wait there and a train would come in at 12:10 at lunch and it left at 12:30. I’d get there and eat lunch really fast and then sell magazine and candy. I was like a checker in there. And then the train would leave at 12:30. It was pretty interesting. Pretty interesting to see the train and that. It had candy and magazines and sandwiches. My mom had sandwiches made and you could buy them there and take them on the train. It was a pretty neat. It was probably my favorite restaurant that they ran.

Jaap: That’s pretty fun. I didn’t know that.

Lester: And then on Utah there was a Boyle’s Bar and the Boyle’s Cafe. I could walk from there to Boyle’s Bar and Cafe. We ate lunch there. It was open from 6 in the morning until 8 at night. And we would eat dinner and whatever. My sister and I would walk up there and eat dinner there. And I guess what I really wanted was to eat dinner at home once in a while. Which is just the opposite of what other people want. They’d like to go to a restaurant every once in a while. But I’d rather eat at home.

Jaap: So did your mom cook at home a lot?

Lester: They cooked all the time. My mom was a fry cook. My mom and my dad, before they got into that restaurant business fully, worked at the Finlen. My dad was a chef at the Finlen and my mother was a cook at the Finlen. She was a breakfast cook. So I was pretty much raised in restaurants. It was pretty interesting.

Jaap: What was your favorite meal that your mom or dad cooked?

Lester: For me it was liver and onions. But you could have anything. I liked food, you know. I liked the way they made liver and onions. Not everyone likes liver and onions, but I liked it.

Jaap: Where did your parents meet? Did they meet at the Finlen or did they know each other before that?

Lester: I think they met at the Arc Light. That was the famous bar or whatever in Meaderville. That’s where they met. And then it was full-blown love at first sight, I guess. I told you my dad, his dad was a druggist. He had the drugstore.

Jaap: And what did your mom’s family do?

Lester: The Canonicas? My grandpa Canonica was a tinsmith. His building is still there. It’s almost from my memory, the shop, the tin shop. There were things there when I was I five. I mean the tin is up on the wall hanging. That’s still there and I’m 79.

Jaap: Does Pat have that building now?

Lester: Yes. When we come from the Archives, he said, “Do you want to go see what we’ve done?” So we keep in touch that way. And his mom was Cora. My mom went as Lena. And I have a sister, Paulette. Paulette is in the house in Portland. She lived with my mother until my mom died. She has three girls.

Jaap: How many siblings did your mom have?

Lester: We’ll start at Frank, Cora, Steve, Lena, Tony. Tony, yeah, he’s the baby. And then Mary-Ann is the baby of the girls.

Jaap: What was your grandpa’s name?

Lester: Anton.

Jaap: Anton Canonica. And he ran the tin shop?

Lester: Yeah. And he always wore . . . In the kitchen. Their home was at the tin shop. But there was. The kitchen was there. And there was a big desk. And I sat at the desk. There was a phone there and I always played office. That was when I was about 5 or 6. And there was always on the table, every day, bread and it was cut up. There was wine right there. A little cruet of wine. And there were those little brown plates and you could put a little wine in there and you could dunk the bread. And they let me do that, but I tried it, but I liked the bread better. I did have a dab of the wine. It was always there. Nobody ever said anything, “Don’t touch the wine.” And I think that was a tradition of Italian descents [sic]. But I know that is unusual thing to see a 5-year-old dipping bread in wine. But they never said a word. Therefore it didn’t seem to me that it was bad. I didn’t like it then.

Jaap: You just wanted the bread.

Lester: So.

Jaap: So did Tony take over working there?

Lester: Tony never worked in there. He always had his shop. His second hand store. The thing about Tony - when my mom would come in from Portland or wherever she came from - we we’d go visit Uncle Frank and Uncle Steve. And Uncle Tony when you went into the store, he’d say, “I’m not selling anything today. You can’t have anything and I’m not giving you anything. He started that all the time. “What do you want?” My mother would use kind of bad language. And say, “I came to visit you. I didn’t come to do it. If I wanted something, I would take it.” But she never did. And he did this same thing to Auntie Marianne, too. And to me. Paulette, my sister, one day she went to the second hand store and she cleaned it all up. And she got yelled at by him. “I had those things in those places and that’s where I want them. Put them back the way they were.” And, of course, my sister is a little bit more outspoken than I and she’s 5 years younger than I and she said, “I’m not doing that” and she walked out of the store. So Tony had to do it himself. I’m not sure if he ever did it or not.

Jaap: So did he ever sell anything? Or did he just do it to collect?

Lester: I actually don’t know. I often wondered. When we walked in there, I’m assuming his relatives always wanted something from him, but none of them did.

Jaap:,: I hear stories from other volunteers here about going in there. They’d say the price and it was always something outrageous. Like $300.

Lester: Like an old broom.

Jaap:,: Like he’d say $300. It wasn’t really for sale.

Lester: Yeah. My dad and him did not get along. My dad bought a refrigerator without a motor. He didn’t know it didn’t have a motor in it. So my dad was pretty upset with him for the rest of his life.

Jaap:,: He bought the refrigerator from Tony? Oh no.

Lester: That was when they were just young, you know. And it didn’t have a motor . . . No, it was a washing machine. And so that stuck in my dad’s head, I think his whole life.

Jaap: Well, I assume if you think you’re buying a washing machine. To go home and learn it doesn’t have a motor.

Lester: But they didn’t dream to think it wouldn’t. Who would think they’d sell you one without a motor.

Jaap: So do you want to go back to how you talked about when your parents moved and you wanted to stay?

Lester: Ok. I went with Mrs. Grey. Now my mother told fortunes, besides cooking.

Jaap: She told fortunes?

Lester: Yes. She was very good at it. And she would read cards. Now, not tarot cards that people have. Playing deck of cards. And she would read cards to you. And she would always read tea leaves. My favorite thing was tea leaves because the tea leaves when you read them and you dumped them out and they went all around the cup. That was for quick. And she was usually, I’d say 9 out of 10 when she read my tea leaves it came true. And same with the cards. I stayed away from the cards because those cards were . . . It was scary.

Jaap: Was it?

Lester: I don’t know. It was more serious. And I know people don’t believe in people that read cards. They’d call her a witch or something like that. But she had a clientele. And Mrs. Johnson is who I went to live with. And she came every week to have her cards read. And that’s when we lived on Nevada Street. And she came every week. And of course my mother had readings and they would come. We had to sit away, because it was a private thing. She had lots of insight. Now my husband, Tom, said she was just a good reader of minds. She would read people, not the cards. But she was usually right. Captain Cahill who was a highway patrol guy, he was a captain then, he came all the time. And I was going to Marquette. This was when I was a sophomore in college and Joan, Bren and I decided to chase our boyfriends to Milwaukee, because my husband Tom got a scholarship to Marquette. And he said, Captain Cahill, this is a true story, he said, “Betty I want to read your cards before you go to Marquette, to go to Milwaukee.” And I said, “really?” And he said, “Yeah, I do.” And I said, “Ok, but . . .” He’s never read my cards. And I wanted him to read tea leaves, but he wanted to read cards. He said, “You’re going to get married, not right away, but in a year, when you go to Milwaukee.

And your first child will be a girl and you will have three boys.” I said, “OK.” And, “Tom will finish college. And you will finish college, but you will finish college much later. One of your children will be first a girl and then three boys and you will have a couple of miscarriages.” I didn’t think about it until, putting it together and why I’m telling you this way is I didn’t think about that until one day it just hit me. . . Tom and I were arguing over, my mother was still alive, and I would always have my tea leaves read when we’d go back to visit her. And he said she’s just a good observer. She’s a bartender and she pays attention to people. And she did. But she had something else. And so did Captain Cahill. So I have a history of that. Now my sister can do that. And I can do that, but I don’t like it. I like it, but I don’t want to meddle in it, because my mother was good at it. And according to my husband, Tom, she’s a good observer of people because she’s a bartender and she works with people and she reads people. That was his answer to that.

Jaap: Where did your mom to do that? Has your family done that for a long time?

Lester: Nobody in her family did it.

Jaap:. And so she just did that out of your house?

Lester: Oh yeah. So she’d say to us. I would need a new pair of shoes or an Easter outfit or something like that. She said, you better vibrate the money. So Paulette and I vibrated the money. I don’t know if that makes sense to you.

Jaap: Not really. Can you explain?

Lester: Well, we’d put it out there that I needed . . . Mother, I don’t know, she would get a dollar for a reading. Money was, you gotta remember where we were with money. So we had to do a lot of readings. But shoes weren’t $99 dollars. So Paulette and I would vibrate our Easter outfits. But . . . usually it worked. But . . . I don’t know if that’s interesting to other people.

Jaap: I don’t know. I might start saying that.

Lester: My mother would say, “Well if you need that, you’d better vibrate it in.” And then the thing that I really didn’t really think happen is to have four children and a couple of miscarriages like he told me. And he read that in the cards. And they’re not the tarot cards.

Jaap: Just a plain deck of cards.

Lester: Yes, like you play canasta with or whatever. And every once in a while I’ll go, this is going to happen. If you’re worried about that. Something. I’ll worry about it for a minute and I’ll think about it and I’ll go ok this is going to happen. But, that’s because, I don’t know, I wouldn’t say that’s a prophecy or anything. It just . . .

Jaap: I think, Lee, you know, Lee. She’s talked about her mom. Would you call that an ability? She can do uncanny things like that. They just can’t quite be explained.

Lester: Tom’s answer to that was . . . I will tell you one day, she was reading my cards, because I usually didn’t do that. And I said would you read my cards. This was when we were in Butte up on Quartz Street. She was reading my cards and saying you’re going to do this and this, but she said there’s going to be a death soon. And I said, in the family? And she said no, a death of a friend. And she said, I’m going to be making potato salad for this funeral. And I looked at her and said, Oh for crying out loud, that’s a little off of it. And sure enough Tom’s best friend died. And she made potato salad.

Jaap: Oh wow, that’s so interesting.

Lester: And I told that to Tom and he said, I said, She wouldn’t know. She wouldn’t know. I said, Is it a relative that’s going to die? And she said, No, it is a good friend or something like that. And then we found out that he died. I said, what do you think about that? And he said, it’s just luck. But I think he was afraid.

Jaap: So, Mrs. Johnson, let’s go back to Mrs. Johnson. She always came to get her cards read by your mom. And then that’s who you went to live with.

[00:19:36]

Lester: Her husband died. He died before I went to her house. I can’t say how long he was dead and she was alone. I said to her that Mom and Dad, I think, they are going to Spokane (and they moved on to Portland). I said, I want to finish school, and her husband died, did I mention that? I want to finish school at Central because I’m going to graduate and I had a job at Pay and Save. I was a checker. I started checking at Pay and Save when I was 15. My sister-in-law, she wasn’t my sister-in-law yet, she was Tommy’s sister. She got me the job. So I had a job. So Mrs. Johnson . . . Mrs. Grey, she was then. I told her I could help you clean house and I would go to school and I would follow the rules and I will cook dinner and wash and whatever. She was a widow and so it worked very well. She was very talkative. She was very smart. She listened to me and I cleaned house. I liked to clean house and mow the lawn and stuff like that. She liked Tom. I was going with Tom since I was a junior.

I went to live with her in the Drives. Then she got a boyfriend. She was going to get married. I asked when she was going to get married so I could find another place to go because I assumed when she got married she wouldn’t want me hanging around. But she told him I wouldn’t get married if you weren’t part of the package. I said, Really? That’s when she was Ruth Grey, and she married Johnson. But he liked me. I was a pretty nice, congenial kid and I said I would do all of that stuff - do the dishes, vacuum or whatever. I liked doing that too. But I still have to work and I want to pay. I did pay some money. When it was through, she gave me my money back. But I wanted to pay. She didn’t take. I didn’t make that, it was good money for me. He was a little bit older, but he was a really nice man. He was a widower for awhile and his son died in World War II and they never had any other children. It was on Farragut street. It was his house, a big white house on Farragut. And we lived there. She had a son. He was away. He was older.

Jaap: Did you stay close with her after you went to college?

Lester: Yes. She got a job as a librarian, I can’t remember the name of it, the school where she went. She let us live in that house, Tommy and I, for a year. I said, we will pay you, and she said, no just keep it up. Keep the lawn mowed. You know, keep it up. Her son came back and they wanted to move back in. We had to face the music. I did try to pay her. And then we went on. Tom taught at Butte High School for 40 years.

Jaap: OK. You guys went to Marquette. Tom went to Marquette. And you went with him. What did you do after Marquette? Did you guys come back to Butte right after?

Lester: No, we went to Medicine Lake, Montana. And he taught school there. And that’s way up in the High Line. It’s quite an awakening to come from Milwaukee to go to the High Line. There was only 202 people there, then, in the 60’s. And Tom taught. And . . . A cute little story in Medicine Lake . . . We were going to go to a party. I told Tom, I don’t feel well. And he said, You’re always saying you don’t feel well, blah, blah, blah. I said, OK. Well, we went to the party and we came back and I was really sick. And I got sick. I went to go throw-up and I didn’t take my false teeth out and Tom flushed my teeth down the toilet.

Jaap: And you were at the party when this happened?

Lester: No, after the party. But, I was supposed to teach Spanish the next day. And I had to cancel because you can’t teach Spanish with no teeth. I had to go from Medicine Lake to Plentywood to the dentist to get my teeth. It took a week or so before I could get the teeth made and all that stuff. I couldn’t teach Spanish and I wanted to teach it because we needed the money. Anyhow . . . I made it through with no teeth for a week.

Jaap: That’s pretty funny. I bet he didn’t ever flush them down again, did he? Or make fun of you for being sick.

Lester: I didn’t say, I just, I just laughed. The people that knew us and stuff, they just laughed and didn’t pay any attention that I didn’t have any teeth. But it was still embarrassing.

Jaap: So how long were you in Medicine Lake?

Lester: Well, Tom wanted to get out of there. I think he wanted to quit. I said, we can’t leave; we don’t have any money. What you see right now is . . . we have to stay there and finish the year. He said, “I want to tell you right now, I’m not staying any longer than that.” And in that town they were pretty close people. They were rich wheat farmers and they didn’t like teachers because we were lower. We were down the social scale. They made it pretty clear too. But Tom was really, I’d have to say, a very gifted teacher. He was very good at Tech. He was a good professor. I have lots of people that I talk to now that say, I knew Tom he was my most favorite college professor. He was very thorough. He was a good teacher.

Jaap: So when you were in Medicine Lake did you have any kids yet? Or was this before when-

Lester: I had two kids. I had Chris and Dennis. When we moved back to Butte and Tom got a job at Butte High and taught for 40 years.

Jaap: What’d he teach at Butte High?

Lester: Sociology and psychology.

Jaap: Did you work during that time?

Lester: I checked groceries. All through high school I checked groceries like I told you at the Pay and Save. I checked groceries.

Jaap: When did you guys go to Missoula? Was it much after that, when you guys went back to school?

Lester: Tom got his master’s degree at Dillon. I had my two-year. He came home one day and he said, I can’t do it anymore. I can’t stand losing. He went from Butte High to Tech to help Ed Simonich coach football and stuff like that. He said, I want to go get my doctorate and that’s how he ended up head of humanities.

Jaap: And he got his doctorate in Missoula?

Lester: Mmmmhmm.

Jaap: And you went to school in Missoula too?

[00:36:00]

Lester: I did. And I drove to Dillon to get my master’s degree. It was in the summer and I was driving and Doctor Block. I was finalizing my master’s. Doctor Block hated people from Butte. I had to take that class from him. Right away, there were three of us from Butte going to school and he point blank told us that people from Butte weren’t reliable. It was really hard on us. Every once in awhile he’d make a remark to the three of us girls. I often wonder if he said that to the men. Anyhow, I took a science class from him. I had to look for roadkill for this thing. We were supposed to go and do some stuff with the roadkill. This was like 7:00 in the morning and I had to be there at 8:00. So I was going down the highway to Dillon and I’d see a roadkill and I’d jump out with my green baggie and my shovel and I’d put the roadkill in there. And Doctor Block, I was afraid I was going to be late and then he’d probably kill me worse.

Because he would. Of course, I was 5 minutes late. Well, I’ll finish that . . . So I’m down there picking up roadkill and the police stop me. The cop came out and he said, what are you doing? And I said, you’re not going to believe me, but I’ll tell you anyway. I’m going to college at Dillon and I’m taking a science class and my assignment is we’re supposed to pick up roadkill and we’re going to boil it and see what animal it is. He looked at me and said, really? I said, do you really think I want to pick up roadkill? Now, I’m being sassy to the policeman. He’s going to do something to me. He looked in the sack to see if I really was getting roadkill. I showed him in the sack. I’m really going to be in trouble because this really isn’t good roadkill. And he said, Naw it’s not too good. Usually there’s good roadkill on the thing.

He said, I’m going to let you go, but I’m going to watch you for awhile. I was terrified of him and then I had to go see Doctor Block and I knew I was going to be late. Because he said we were all lazy from Butte. Of course, I’m a Butte person right to the end of the earth. I really didn’t appreciate, I would never, if I didn’t like Missoula, I would never pick on somebody from Missoula. Anyway, I’m going down there and he’s following me kinda. So went ahead and got my roadkill and got to the class and everybody in the room and I’m late, but I was only maybe 4 minutes late. They know I’m going to get killed because they know he doesn’t mince words. He says, you’re late. I says, yes, I’m sorry. Why are you late? I said, you told me to get roadkill. So I was going down the road and I started out at 7:00 or earlier than that, it had to be 6:30 because I had to be there at 8:00. It was about 7:00 when I was on the roadkill. He looked at me and said, did you get roadkill? And he said, why are you late? And I said the policeman stopped me and asked me what I was doing. I had to tell him, I had to get roadkill that’s my assignment from you, but I’m going to get some, but I was polite and he said, You did, huh?

Well, I happen to have a refrigerator of dead rabbits. So he takes me into the freezer and shows me all the dead rabbits. Why didn’t you tell me that and let me have a rabbit? I did say that, like that. He said, you didn’t ask. I said, I didn’t know you had frozen rabbits! Anyhow, he was a little bit nicer to me after that and to us girls. He would single us out which we never did understand what the other guys did so bad. Oh, I know what they did, they worked in the mine and they were usually 5 or 10 minutes late. They worked nightshift and then they got in the car and drove to Dillon.

Jaap: That doesn’t sound too lazy to me. Can you imagine?

Lester: I don’t know. So anyhow. That’s that. That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

Jaap: I think it’s fascinating that when you guys were in Missoula, how many kids did you have?

Lester: Four.

Jaap: Four kids and you guys lived in a trailer?

Lester: 12 foot trailer

Jaap:. I think that’s fascinating

[00:43:00]

Lester: We had fun of it. A couple things that Mikey. I had to go get Tom from this thing. There were people going to school kind of like us. We made friends with the neighbors and they were from Pennsylvania. They had kids too. It was like 92 and it was hot. I said, could you just kind of keep an eye on my kids, I have to pick Tom up. I’m meeting him under the tree by the whatever, I can’t remember the name of the street. I said, it not going to take me no more than 10 minutes to get to him and 10 minutes back so I’ll be gone 20 minutes. She said, fine. And actually Mike, they had a bike there. We had a bike there and he rode his bike and that and they were all playing. Then Mike decided he would climb the tree and he was swinging and he hung himself. He had a rope burn around his neck.

The bad part about that was he looked like he hung himself. You could see the burn mark. On top of that, the day before that he was walking, we were going to the game room and he opened the door and he tore his big toenail off. So he had a hanging thing like that and his toenail. He couldn’t wear shoes. He had to wear flip-flops. He looked like somebody tried to kill him. It was awful. Tommy and I, we both said, they’re going to put us in jail. They’re not going to believe us. Really, Mike did it to himself. But it was, you know, we made it.

Jaap:. When you were in Missoula, did you guys have your house in Butte still?

Lester: We rented it for the summer. And then the people wouldn’t move out because they liked the house and the neighborhood.

Jaap:. Oh no. How did you get rid of them?

Lester: I said I’d go to the police, you know, because we agreed. We could only rent it to them for three months while they were finding a house. That house was a pretty nice house. It was in a nice quiet, really nice neighborhood.

Jaap: Was it on Quartz Street?

Lester: Yeah, on a dead end street. Right under the IC [Immaculate Conception] church.

Jaap: Yeah, that’s a lovely spot.

Lester: It was really quiet then. This was back in the 60’s. We did get them out. Then Tom decided he had to go to Missoula and finish his last year.

Jaap: You had all your kids here. What did you guys do growing up over there. They grew up in that Quartz Street house. Did you stay over there the whole time?

Lester: In ’98 we sold our house. We bought the land at Silver Star at Jefferson Acres. We took our camper and parked it there. So we bought an acre. That acre only cost $2200.

Jaap: What does it cost now?

Lester: $39,000.

Jaap:. Isn’t that crazy

Lester: I looked at it. It was hard for us to get the $2000.

Jaap: Right.

Lester: We lived at that Quartz Street until ‘98. Tom’s sister, Kay, sold that house to us for $15,000. It was a two story house. It had three bedrooms. That neighborhood there were 18 kids in that half block. And they had all the same age. You know, different ages. You didn’t have any . . . We all watched each other. I don’t know if you know Joan Roach. Dr. Roach the dentist. They lived on Copper Street. That was a dead end street too. We were just right under the IC school. I taught school at the IC.

Jaap: Yeah, you taught school at the IC. How long were you at the IC?

Lester: 5 years. Then I graduated. I went to Dillon and all that. That’s when I was getting roadkill and all that stuff.

Jaap: Where did you go after the IC? Where did you teach after that?

Lester: I got a job. I got my four year degree and I got a job. I got a job at Kennedy. It was just a school. School was just going to start and they didn’t have a teacher and I happened to walk in and give them my credentials and they said, well you can go to Kennedy school. I said, ok. That was in ‘64. And I was there for 32 years.

Jaap: When did you retire?

Lester: 2000.

Jaap: And then Tom taught up at Tech and coached football.

Lester: And then he became a professor of sociology and he became a professor and headed the department of sociology and technology. He started instigating that nursing program.

Jaap: Did he?

Lester: He started it. Tech is having a hard time. They need other things than engineering. So he started that. He didn’t get it all the way through. It took a while.

Jaap: I didn’t know that. That’s a really great program.

Lester: Well it wasn’t great then. It was in the baby stage. You had to convince the engineers because they thought the only important people were engineers.

Jaap: That’s how engineers think, isn’t it?

Lester: Well, you see, I have three children that are engineers. I have one that was smart that became a . . . money guy. He got a business degree. He got a business degree from Tech.

Jaap: Did all of your children go to Tech?

Lester: Chrissy is a mining engineer.

Jaap: Where are your kids now?

Lester: Chrissy is in Fort Collins. Steve, the baby, is in Boise. Mike’s in Minneapolis. Steve’s the guy with the business degree. The rest of them . . . Mike a petroleum engineer. Dennis is a petroleum engineer. Chris is a mining engineer.

Jaap: And Dennis is here right?

Lester: Dennis is where I live.

Jaap: Ok Betty, well, I don’t know if I have any more specific questions. Do you have any other stories you wanted to share? Or anything you can think of?

Lester: I think I told you all of them.

Jaap: Did you tell them all your secrets? All your lies?

[00:53:00]

Lester: I was thinking . . . of stupid things that happened to me. When we were in Milwaukee, I was teaching in a Polish community. I had to ride on the bus. Well, I was sick and I got sick on the bus. I had to have the guy pull over and I had to throw up and stuff. I was on the bus at 7:00 because I had to go to South Milwaukee. Now this is in Milwaukee when I’m going there. I was pregnant. I said, Could you please stop the bus? And he said, Why are you sick? And I said, I am expecting a baby. And in those days, if they found out you were expecting a baby and you were teaching school, you were gone. I had to keep it quiet. So I could only work until I was about six months pregnant because then I started to show.

That was bad. I never did understand that. Anyhow, the next day when I got on the bus . . . I was on the bus with all the guys who were going to [unintelligible]. They built car parts. They called me Little Mother. The guys, I was scared of them because I was the only lady on the bus. Of course, I was sick and then I had to tell them I was pregnant and I was sorry I was sick. And then they called me, Little Mother. I thought that was really nice. “How are you feeling, Little Mother?” “Are you getting better?” And then the bus driver had a plastic thing so I could throw up in that. But I preferred not to do that because I didn’t want him to have to clean that. So anyhow, they called me Little Mother.

When I had to quit because it was at the sixth month and I was showing and I had to leave and I had to leave and they were sorry that I was leaving because they always looked forward to that. I said, I’ll missing hearing you talk and stuff like that. I was lucky. Of course, I’d talk to anybody.

Jaap: So at the school, did you tell them at one point or at some point did they just say, “Are you expecting?” Did you approach them or did they approach you?

Lester: When I was sick and throwing up . . . I was teaching in a Catholic School. So she comes in the room and she’s feeling sorry because I am sick because I have to leave the room and throw up and something like that. She brings in a brown bag some brandy. She said this ought to help your stomach. I said, I can’t drink alcohol when you’re pregnant. She said, Well, it will calm your stomach down because we don’t want you to leave. I said, I have to leave that’s the rules. She said, well we’re going to work on it and we’re going to keep you until you can’t. They were really good to me. And I was good to them. I ended up teaching, I was teaching 4th grade. And the nun that was teaching 2nd grade fell off the altar and died. And they came to me and said, we’re going to change you to 2nd grade. I said, OK, that’d be a little bit easier. She said, the only thing is, is there are 60 second graders.

Jaap: For one teacher?

Lester: Well this is Barbarian Time. In teaching school it was barbarian. They were kind of disrespectful.

Jaap: How many kids did you have teaching 4th grade?

Lester: 40. But, I’ll tell you what, they said they’d take care of me. If I needed help with the 60. Well school was different then. The parents were Polish. Half of them couldn’t speak English. They wanted those kids to go to school and if they acted up, those parents came and almost murdered the kid.

Jaap: Not like now.

Lester: Their kids are perfect. They wanted to fit into the United States of America because they came from Poland. Half of the parents I had, when we had parent-teacher conferences, I had to have a translator.

Jaap: That must have been a challenge.

Lester: Very interesting. The only thing I can remember from the Polish now is pączka day. And that was “donut day.” And that was pączka. That was the name of the donut. Every first Friday was pączka day.

The next year they asked me back, but I didn’t have to have 60 students. I only had to have 40.

Jaap: Well, what a relaxing time you must have had, Betty. I can’t imagine having 60 second graders.

Lester: But, you see it was a different world. Those kids were told, listen, you can’t speak English too well. You’re going to school and you’re going to behave. Whatever they did to them at school, they said, they’ll get worse at home. So the parents did their . . . I didn’t really have to . . . There were a couple kids that were kind of naughty, but they were challenged kids. And they said, well, you will only have to have . . . you won’t always have 60 kids. In October, they had to remake their first communion and they were going to put them in a school because they were deprived . . . they need more help. So the five, they were kind of retarded. I don’t know how to say it without being rude. They needed help. So there were five that were leaving so then I ended up with 55. But that was the only year I had to have 60. The rest of them were only 40.

Jaap: That’s amazing.

Lester: Well, it sure got you into training.

Jaap: When did special needs start being offered in the schools? When did they start those classes up?

Lester: It got better, yeah.

Jaap: Before, were they just incorporated in classes with all of the other kids before?

Lester: Actually, those 60 second graders, there weren’t always that many, but there were 40 kids mostly.

Jaap: Those are big classes.

Lester: But that was in 1960, let’s see Tom graduated in ‘61 or ‘62, so it was Barbarian Time. I call it that because . . . But actually, I think, in the Catholic school, I know that wouldn’t have happened in the public school. That wouldn’t have happened in the public school, you wouldn’t have 60 students, but the nuns handled it quite well.

Jaap: I’m sure they did.

Lester: We could hear . . . when I was going to school at Saint Joe’s and I was in 8th grade and I was coming down the steps. It was after school. I said, the principal’s name was Sister Mary Generose, but I was coming down the steps then and I turned around the corner and I said, Jiggers, there’s Jenny. And she took me into that classroom and she heard me and she said what did you say? I said, Jiggers, there’s Jenny. And she said, What’s my real name? I said, Sister Mary Generose. She said, If I hear that again, you’re going to write Sister Mary Generose 500 times.

Jaap: Yeah, I bet she didn’t hear it again, I’m sure.

Lester: I said, Thank you, Sister. I was terrified. But I didn’t think that was a bad thing anyway. But it was at the time. Now, that wouldn’t . . .

Jaap: Now it wouldn’t phase anyone. Then did you go to Girls’ Central?

Lester: Mmmhmmm. I went to Girls’ Central and that’s when I went to, my Junior year, my mom and dad went to Portland or Spokane.

Jaap: Why did they decide to leave?

Lester: I never did ask them. We also had . . . This is just a sideline. We have land 15 miles away from Butte. 98 acres of land in Silverbow, in Price’s Gulch. It’s only 15 miles away. We had a cabin there, built a cabin there. But my grandpa’s cabin, my grandpa Canonica’s cabin, is still standing. I think it’s gotta be 100 years old.

Jaap: Did you guys go kind of vacation out there?

Lester: No because Tom didn’t like it, because Tom would rather go fishing. We did go out and visit it and stuff like that. But Pat Mohan and I, we’d go together because it’s his mom’s too, but his mom’s passed away.

Jaap: When you were younger though did your parents take you out there?

Lester: When I was younger, yeah, until sophomore year in high school.

Jaap: What’d you guys do up there?

Lester: Basically hiked but the other too is . . . it’s situated . . . all the roads were dirt, of course. There was a road on the top of the hill of our land, you could drive to the swimming pool at Gregson.

Jaap: Oh really. That’s kind of perfect.

Lester: But you can’t do it now because that road’s gone. But, nobody believes me, but I remember. I took Tom up to the top of the hill and said, you can kind of tell that there was a road there. But it was kind of scary. But my dad was a car person and he could fix cars. And he changed cars. He could do anything. Well, him and my mom built that log cabin together. And they drug those things and pitched and pulled that skin off and stained it. It was really a nice cabin when I was little.

Jaap: That’s fascinating. And it’s still standing?

Lester: Well, my grandpa’s is. They didn’t put it on a good foundation. But you see my grandfather, I didn’t know, it’s some kind of cement because it’s still there. And it’s chinked really good, you know.

Jaap: Yeah construction was a lot different.

Lester: Well, even that tin shop on Arizona. He built that.

Jaap: Did he build that? Anton did? Canonica?

Lester: The grandpa.

Jaap: I didn’t know that. I don’t know how old that building is.

Lester: It’s pretty old. And there’s in that thing. There’s a thing where you build stove pipe and every time I walk in there when I was about 4 or 5, I’d run right into that and hit my head. I still remember it. I think I cried for two years. Do you have some other questions?

Jaap: You hung out at the restaurants and stuff when you were little, but what else did you do for recreation?

Lester: I played volleyball. Fieldball.

Jaap: Fieldball?

Lester: Fieldball is the girls’ answer to football. Well, there were 9 of us. You’d kick the ball and you’d get your points.

Jaap: Like a soccer net?

Lester: I played that. We were champions in that at Saint Joes. Then I played volleyball. We’d practice. We had to go up to that Saint John’s church. That was the only gym in town for Catholics. Girls weren’t supposed to do stuff like that.

Jaap: When did you say you were born? 38?

Lester: So it was like 48, when I was in 8th grade or something like that. Because I graduated in 56 from high school. Girls weren’t supposed to be playing games like that. But actually it was a fun game. I played volleyball. Fieldball, I think we were champs. We used to walk up. Imagine that, from Saint Joe’s we’d get out of school and walk up to Saint John’s, practice volleyball and walk back home and stop and get a sugared ice-cream cone.

Jaap: Where’d you get the sugared ice-cream cone at?

Lester: You know where that Metals Bank, that big building that used to be there. There was an ice-cream store.

Jaap: In the Rialto?

Lester: I’ll have to go look at that and tell you.

Jaap: But there was an ice-cream shop down there?

Lester: And it had all sorts of stuff. They had more ice cream shops.

Jaap: We need to bring that back, I think.

Lester: They closed up and stuff. We’d come from Saint John’s Church where we practiced in the gym and stop there and get an ice-cream cone. But we only got to go Tuesday and Thursday to use it.

Jaap: Did you go to the theaters often?

Lester: Yeah. If we were really lucky, we went to, I was the oldest, I took my sister, Linda and my cousin, and if there was a really good show and we were really lucky, that was a quarter. That would be like going to the Rialto or the Montana. Down from the Rialto there was the Park Street film thing. It was usually black and white and that was a nickel.

Jaap: So you could go to that?

Lester: I didn’t like it, but the one across the street from . . . on Main Street. There was the American Candy Shop and there was the American Movie Shop too. And that was 14 cents.

Jaap: Can you believe it?

Lester: And then going down the street. Going down Utah, there’s a place where they do fights.

Jaap: Oh the boxing?

Lester: That used to be a grocery store. That was called, Lind’s. We would get ice-cream there. There was an ice-cream shop next to Lind’s. So that was all close to Nevada Street where I lived.

Jaap: Did you go to Columbia Gardens often?

Lester: On Thursday.

Jaap: Thursday, that was Children’s Day?

Lester: All day for a nickel. On Thursday, if you got on the bus, it was free, because that was Children’s Day.

Jaap: So did you ride the bus to the gardens?

Lester: Yes, and take my sister.

Jaap: What was your favorite thing to do there?

Lester: Ride the rollercoaster. I couldn’t ride the airplane because I would get sick. But the rollercoaster was a quarter. You had to save your . . .

Jaap: That’s kind of a lot, when you think about going to the Rialto was a quarter. A rollercoaster for a quarter.

Lester: Yeah, but the other rides were like 14 cents or something like that. I couldn’t do that airplane, going in circles like that. I’d get carsick. I liked it, until I got carsick going in circles around.

Jaap: They could just do a few circles less.

Lester: Could you let me off halfway? But the rollercoaster was nice. I didn’t care much for the merry-go-round with the horses.

Jaap: The carrousel?

Lester: But I went with my sister because she was ok. It went up and down, the horses went up and down. There was a seat there where I could sit and I sat there, because I couldn’t do the up and down. I couldn’t even hardly do that but I had to do that because Paulette was 5 years younger than me.

Lester: Thank you for the interview.

Jaap: Thank you, Betty.

Lester: Done with me?

[END OF RECORDING]