Butte, America’s Story Episode 72 - Germania

Welcome to Butte, America’s Story. I’m your host, Dick Gibson.

The mines west and north of Butte were some of the earliest to develop because the Butte mineral district is zoned like an onion, with the outer rings richer in silver than the central, more copper-rich sections. While the Orphan Girl was probably the most prolific producer, at more than seven million ounces of silver, other mines were important during Butte’s silver era, 1875-1893.

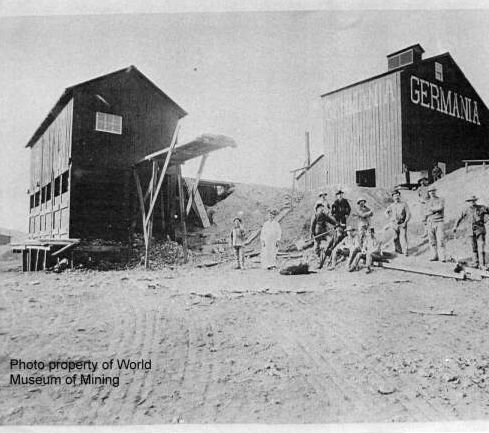

The Germania mine was about a half mile almost due south of the Orphan Girl. It was established by a German immigrant about 1881. He promptly died, and his nephew, Louis “Lee” Freudenstein inherited the claim when he came to Butte in 1882. Butte’s silver boom really began in 1884-85, and by November 1885, the Germania was “being worked night and day… looks very well,” according to the Butte Miner. Freudenstein and his wife Christina were living at 211 West Galena, a tiny frame house long gone, on the site of today’s Headframe Spirits building.

In 1886, the Germania was being worked aggressively. In January that year, the 150-foot level encountered an old drift from the Mountain Boy mine northwest of the Germania. The Mountain Boy had been abandoned and filled with water, and the onrushing torrent blasted the two Germania miners, Gus Anderson and James Oxman. Oxman, a 25-year-old Cornwall man from Redruth, England, was carried away and drowned, but Anderson survived. It took a week to dewater the mine and remove the debris to retrieve Oxman’s body. The owners of both mines, Freudenstein for the Germania, and J. Ross Clark for the Mountain Boy, were found negligent, but I don’t know what penalty they paid, if any.

Later in 1886, the Germania had 20 men working following the discovery of a rich 10-foot vein that showed assays reporting as much as 15,000 ounces of silver per ton – incredibly rich, with nearly half a ton in silver. Fifty, 100, even 1,000 ounces per ton were often reported in Butte’s western mines, but the Germania find was a “veritable bonanza,” albeit short lived. For comparison, today the Montana Resources Continental Pit gets a silver credit of about 0.07 ounces per ton.

By 1891 the Germania had two shafts, 150 and 200 feet deep. They reported gold at 100 ounces per ton with several hundred ounces of silver. Freudenstein’s fortune was made, and he was building a nice new duplex at 403-407 West Mercury in 1899 when he died. His widow Christina and her seven children continued to live there for many years, and the home is still standing. It was part of Butte Citizens for Preservation and Revitalization’s Dust to Dazzle tour in 2014. Christina managed the mining properties as well, and her son Louis was elected to the Montana state legislature as well as serving as Butte city auditor. Christina died in 1933, remembered by hundreds of friends as one of Butte’s pioneering women.

The Germania was owned by the Butte & Superior Mining Company in 1918. They extended the main shaft to 1000 feet and the longest drift to 500 feet, and added two additional shafts including a steep incline down to 270 feet. Production then was zinc and manganese more than silver, and in 1925 the mine was one of Montana’s leading zinc producers.

Operations for manganese and zinc continued into the 1950s, and the Germania shafts were backfilled and bulkheaded in the 1980s and 1990s, but the extensive dumps remain. You can find the foundations of two rectangular brick buildings at the site, and along one path irises bloom at the likely site of a small residence.

As writer Edwin Dobb has said, "Like Concord, Gettysburg, and Wounded Knee, Butte is one of the places America came from." Join us next time for more of Butte, America’s Story.